RBC Brewin Dolphin Market Update – Fear and Greed

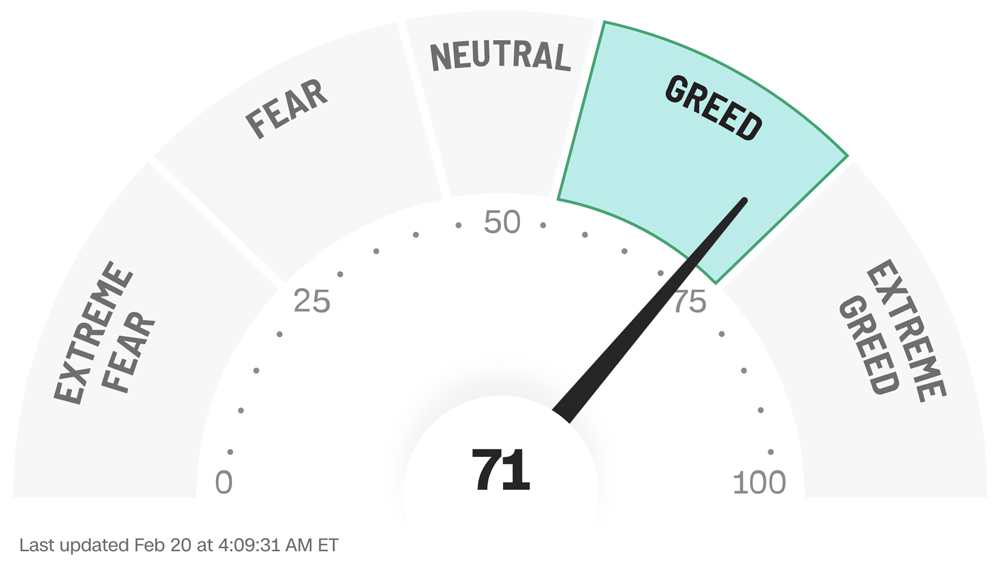

CNN Business produces the “Fear and Greed Index”, a barometer of stock market sentiment. It uses a number of different measures to gauge the mood and whether share prices have run up too fast (that is the Greed factor) or fallen potentially too far (the Fear). As an indicator, in our opinion it is best used to show how our own feelings and biases can affect our decision making. When combined with other tools – including, most importantly, some fundamental research on investments – it is a useful measure of sentiment.

How has it changed over time?

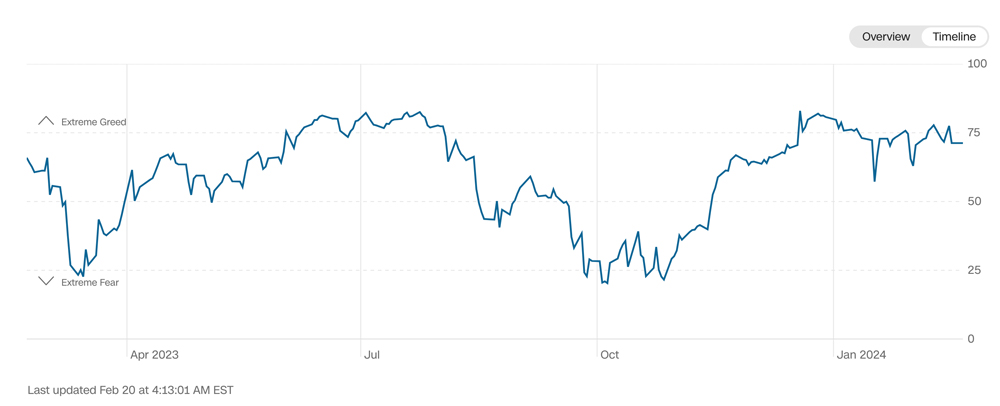

As you can see here, the measure has been surprisingly volatile over the last year, swinging between the two extremes quite markedly, although given the events of the last year, perhaps it should not be that surprising.

This oscillation between Fear and Greed was linked closely to the surge in inflation and the resultant increase in interest rates, as governments around the world instituted a series of hikes to try to cool their economies. After fifteen years of almost zero interest rates, interest rates shot up very quickly to historically more normal levels, but which, nevertheless, came as something of a shock to those who had become used to the narcotic effects of “free money”. During last year, every month’s inflation figure was awaited with the eagerness usually reserved for Euro Million Rollover draws, with investors hoping to gain some sign that pressures were abating and that interest rates had, therefore, reached a peak.

Have they?

Inflation has already begun a fairly quick descent from the highs and this, in turn, means that the upwards pressure on interest rates has also abated. However, there are a couple of flies in the ointment which will only really become clear over the year ahead. Firstly, where will inflation settle? Food price inflation remains high and recent disruption to freight passing through the Suez Canal via the Red Sea, coupled with low water levels reducing traffic through the Panama Canal, has put pressure on supply chains, potentially stoking inflation. Geopolitics has also kept the oil price relatively high, which has slowed the pace at which inflation is falling.

What does this mean for interest rates?

It looks as though we have seen the peak in interest rates and, all other things being equal, we should begin to see rates come down. Certainly, fixed rate mortgages in the UK are indicating that rates will fall, but the question is how quickly? There is no easy answer to this one and it is partly reflected in the swings in sentiment that we saw last year. One month’s data shows inflation is strong and that there are no signs of the economy slowing – cue a fall in bonds and equities as markets fear that interest rates are either going up or not coming down. The next month’s data shows fewer jobs being created and lower sales in the shops – cue euphoria and jumps in bond and share prices. However, having reached a peak, interest rates will begin to fall in due course, but probably not as quickly as some people hope (for the reasons above).

Is this good news for the global economy?

Recessions come in all shapes and sizes, but the technical definition is two quarters of negative economic growth. This can be, as in 2008, a collapse in the global economy or – and this type is far more common – a gentle slowing, with negative growth of a fraction of 1% in total. It is like the difference between a sniffle and flu. While we may have a recession this year or we may not – we simply do not know – it is far more likely to be of the mild variety. In any event (and to get back to the question), a falling interest rate environment is likely to create a more positive business environment for this year and next. Economies are much like super-tankers, in that it can take quite some time before the prow begins to turn and it can take quite some stopping when it does. Running an interest rate policy is, then, fraught with peril and definitely one where a good crystal ball or a skill in reading tea leaves is vital.

What could go wrong this year?

The list is limited only by your imagination. However, unknowns aside (i.e. the things that we do not even know are problems yet), the main issues this year are likely to be politics, the global economy and climate change.

Shall we start with politics?

Politics will certainly come to the fore this year. We need to have an election in the UK by January next year at the latest and we cannot imagine an electorate would thank a government who held an election campaign over the Christmas period. More likely is an Autumn election, with the gamble that the economy will show enough signs of recovery by then for a weary electorate to feel better off and more willing to give the incumbent government another go. With the polls where they are, this is going to be a tough call.

What about the US?

The US is interesting. The more court cases Donald Trump has to contest, the more popular he becomes – or at least the more popular he becomes with Republicans who must choose their presidential candidate. Conversely, although the US economy is doing OK, Joe Biden is not really reaping the benefit. The contest will likely come down to the polarising nature of Trump and whether enough people will vote for a candidate they do not really like to avoid having a president they do not want. However, looking at the increasingly radicalised nature of European politics and the collapse of moderate centrists, it would be a fool who would bet that Trump does not win. In many ways, this reflects the failure of existing parties to be able to deliver any rise in living standards for their populations.

And the global economy?

The Chinese economy has failed to make any progress over the last year, with a collapse in their property market leading to a collapse in economic confidence, as these things tend to do. This has been accompanied by further interventions by the Chinese government on large companies which has, in turn, led to sharp falls in share prices. If there is one thing global investors hate above all others, it is uncertainty over how governments are going to treat their companies. Companies that fall into this boat require a very large risk premium, which is reflected in very low ratings and – on paper at least – very cheap shares. Moreover, once confidence is shattered, it can take a long time to rebuild.

That doesn’t sound so great!

It is better if we look elsewhere. The US economy has continued to perform extremely well, largely thanks to its leading position in new technologies. Indeed, many non-US companies choose to list their shares in the US – Swedish company Spotify and UK chip designer ARM Holdings being two examples. With the much talked about AI, this is not likely to change any time soon, either. What effects will AI have? It actually rather depends on who you ask, but proponents will tell you how it will profoundly affect every industry and revolutionise areas like drug discovery, as vast amounts of data can be crunched easily. Whatever the outcome, it is safe to say that there will be a wall of money poured into the area and it may well be as revolutionary to the way we operate as the Internet has been.

How do we invest with this background?

As we have said before, markets go up and down, economies boom and bust and governments come and go, but it tends not to affect how much washing powder you put in your laundry. We firmly believe that the best defence against challenging markets is a focus on the quality of investments that we hold, coupled with a diversified portfolio of investments. Quality companies lie at the core of our investment portfolios and we are confident that they will deliver solid capital growth and income returns over the longer term. The fairly sudden change in interest rates created a challenging environment, but as the tide turns, we look to the remainder of the year and beyond with some confidence, albeit that there will, inevitably, be a few extra and unforeseen challenges along the way.

As always, if you do have any questions or concerns, please get in touch.